King James I of England and VI of Scotland, c.1606, after John De Critz the Elder (c.1551-1642) National Portrait Gallery

In a previous post I painted King James I in a rather villainous light, pointing out his clearly racist view of New World peoples and hinting that such an attitude, coupled with his hatred of smokers, may have contributed to the decision to execute Sir Walter Raleigh.

E.R. Billings - Tobacco: its history, varieties,

culture, manufacture and commerce, with an account of its various modes of use,

from its first discovery until now. Hartford, Conn. 1875

It

seems that 17th century smokers did not take long to hit back,

avenging their hero’s death.

Sir Walter Raleigh, moments before his beheading in Old Palace Yard, Westminster. British Museum Collection

Following Raleigh’s execution, the Stuart

government desperately tried to justify its action. In an attempt to ‘bury bad

news’ it had arranged for the execution on 29 October 1618 in London to take

place on the Lord Mayor’s Day, the timing being contrived ‘that the Pageants

and fine Shows might avocate and draw away the people from beholding the

Tragedie of the gallantest Worthie that England ever bred’, as the 17th

century chronicler John Aubrey put it.

A further move by the government was the publication of a 68-page pamphlet justifying the execution.The full title was A/ Declaration/ of the Demea/nor and Cariage of/ Sir Walter Raleigh,/ Knight, as well in his Voyage, as/ in, and sithence his Returne;/ And of the true motiues and ìnduce/ments which occasioned His Maiestie/to Proceed in doing lustice upon him,/ as hath bene done.

The Lord Chancellor, Francis Bacon, later to be

disgraced and charged with 23 separate counts of corruption, was the pamphlet’s

principal author, working with the King. In a letter to a friend he wrote: ‘We

have put the Declaration touching Raleigh to press, with his Majesty’s

additions which were very material and fit to proceed from his Majesty.’

The Declaration was no doubt countered by less professionally produced publications which gave the opposite view. One of them, ‘Vox Spiritus or Sir Walter Raleigh’s Ghost’, pictured above, was a handwritten pamphlet, conserved at Trinity College Dublin. It was produced in 1620 to promote the ideals of the late Sir Walter, namely the mistrust of Catholicism and all things Spanish. After Raleigh's execution in 1618 the King of Spain, the Pope and the Devil were seen as conspirators in a new version of the 1605 Gunpowder Plot.

In 1603, when Sir Walter Raleigh was first

confined in the Tower, his violent and haughty temper had rendered him ‘the

most unpopular man in England’ wrote the 18th century historian and philosopher

David Hume. Fifteen years later, thanks due in part no doubt to the spread of

such hispanophobic literature, the same writer stated: ‘No measure of James's

reign was attended with more public dissatisfaction than the punishment of Sir

Walter Raleigh.’

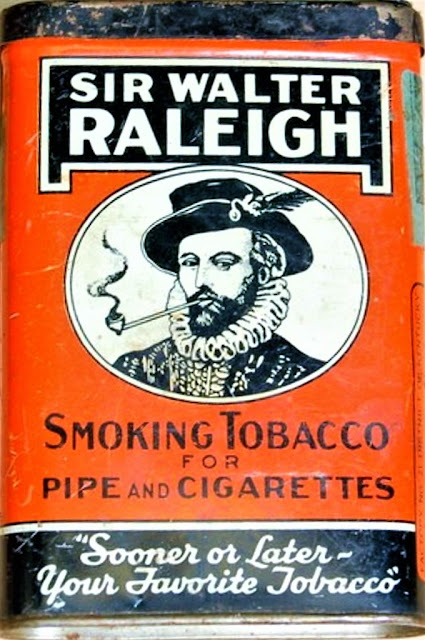

Pipe-makers, as well as pamphleteers, played their part in the defence of Sir Walter. In a fascinating blog post arising from the discovery of what was likely to be a 17th century clay pipe at Bermondsey, in the mud of the London Thames foreshore, Natalie Cohen explains the significance of what were known as Sir Walter Raleigh pipes, such as the ones seen here.

Representing a bearded man being swallowed by a crocodile, the pipe is apparently based on the legend that Raleigh fell overboard during one of his expeditions and was seized by the creature which promptly let him go because it found the smell of smoke so unpleasant. Many such pipes were made in Holland during the 1630s and 1640s.

Why Holland?

It seems that James I imposed harsh restrictions on English pipemakers during his reign and many emigrated to Holland during the early 17th century, explains Natalie Cohen. The number of English pipemakers in the Netherlands rivalled England by the third decade of the 17th century. ‘The Raleigh pipes were made as a memorial to the great smoker, with James I represented as the sea monster or snake “who swallowed Tudor power”’.

Photo of Ashburton Exeter Inn and Raleigh mural taken by John Stickland 26 Oct 2012. Not quite accurate as Sir Walter is seen smoking a cigarette rather than a pipe

The full blog post ‘Walter Raleigh and the Crocodile – the Story of an Artefact’, including the above fascinating images can be found at http://www.thamesdiscovery.org/frog-blog/walter-raleigh-and-the-crocodile

Natalie Cohen’s blog

refers to an article by Diane

Dallal in Smoking and Culture: The

Archaeology of Tobacco Pipes in Eastern North America, edited by Sean

Michael Rafferty, Rob Mann University of

Tennessee Press, Knoxville 2004. Whales as well as crocodiles are part of Raleigh mythology!

I’m sure that Charlotte Coles will refer to this

kind of curiosity in her talk to Lympstone History Society, ‘The History of

Clay Pipes’, on Thursday 22 February 2018.

The significance of personalised pipes, made in Jamestown, Virginia, in the early 17th century, is the subject of an article in National Geographic News, 30 November 2010 https://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2010/11/101129-jamestown-personalized-pipes-virginia-history-colonial-america/

FOR THE RALEIGH 400 CALENDAR OF

EVENTS WORLDWIDEIN 2018 CLICK ON

http://raleigh400.blogspot.co.uk/2018/01/raleigh-400-calendar-of-events-in-2018.html

The significance of personalised pipes, made in Jamestown, Virginia, in the early 17th century, is the subject of an article in National Geographic News, 30 November 2010 https://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2010/11/101129-jamestown-personalized-pipes-virginia-history-colonial-america/

FOR THE RALEIGH 400 CALENDAR OF

EVENTS WORLDWIDEIN 2018 CLICK ON

http://raleigh400.blogspot.co.uk/2018/01/raleigh-400-calendar-of-events-in-2018.html

No comments:

Post a Comment